SLAVONIC TEXT:

Самые лучшие рукописи Греческие хранятся в настоятельских кельях. Их только четыре, но они весьма драгоценны по своей древности, редкости и особенности почерков, по содержанию своему, по изяществу живописных ликов святых и по занимательности чертежей и рисунков.

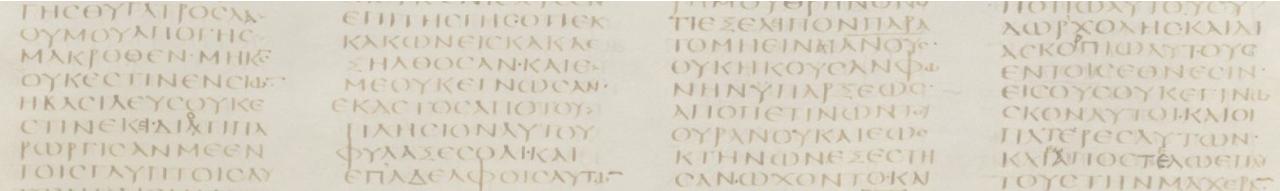

Первая рукопись, содержащая Ветхий Завет неполный* и весь Новый завет с посланием апостола Варнавы и книгою Ермы, писана на тончайшем белом пергаменте в четвертую долю длинного и широкого листа. Буквы в ней совершенно похожи на церковно-славянские. Постановка их - прямая и сплошная. Над словами нет предыханий и ударений, а речения не отделяются никакими знаками правописания, кроме точек. Весь священный текст писан в четыре и в два столбца стихомерным образом и так слитно, как будто одно длинное речение тянется от точки до точки**. Такая постановка букв без грамматических просодий, и такой способ писания священного текста, придуманный Александрийским диаконом Евфалием около 446 года по рождестве Христовом и вскоре покинутый по той причине, что между столбцами оставалось много пробелов на дорогом пергаменте, доказывают, что это рукопись была издана в пятом веке. Она достопримечательная во многих отношениях. В ней усматриваются: особый порядок священных книг, вразумительное изложение Псалтыря и Песни Песней, множество разных чтений на полях новозаветного текста, и особенное наречие. Историческая часть Ветхого Завета окончена книгами Товита, Юдифи и Маккавейскими, потом следуют Пророчества, и за ними Псалтирь, Притчи, Екклесиаст, Песни Песней, премудрость Соломона и книги Сираха и Иова. Далее непосредственно начинается Новый Завет без всякого предисловия. Сперва написаны Евангелия Матфея, Марка, Луки и Иоанна, потом послания апостола Павла к Римлянам, к Коринфянам, к Галатам, Ефесянам, Филиппийцам, Колоссянам, два к Фессалоникийцам и к Евреям, далее его же послание к Тимофею.

*Кроме книг, Товита, Юдифь и Маккавейских утрачены, все прочие исторические описания, и пророчества и пророчества Иеремии, Иезекииля, Даниила, Осии и Амоса.

**Смотри снимки между Син. видами

Самые лучшие рукописи Греческие хранятся в настоятельских кельях. Их только четыре, но они весьма драгоценны по своей древности, редкости и особенности почерков, по содержанию своему, по изяществу живописных ликов святых и по занимательности чертежей и рисунков.

Первая рукопись, содержащая Ветхий Завет неполный* и весь Новый завет с посланием апостола Варнавы и книгою Ермы, писана на тончайшем белом пергаменте в четвертую долю длинного и широкого листа. Буквы в ней совершенно похожи на церковно-славянские. Постановка их - прямая и сплошная. Над словами нет предыханий и ударений, а речения не отделяются никакими знаками правописания, кроме точек. Весь священный текст писан в четыре и в два столбца стихомерным образом и так слитно, как будто одно длинное речение тянется от точки до точки**. Такая постановка букв без грамматических просодий, и такой способ писания священного текста, придуманный Александрийским диаконом Евфалием около 446 года по рождестве Христовом и вскоре покинутый по той причине, что между столбцами оставалось много пробелов на дорогом пергаменте, доказывают, что это рукопись была издана в пятом веке. Она достопримечательная во многих отношениях. В ней усматриваются: особый порядок священных книг, вразумительное изложение Псалтыря и Песни Песней, множество разных чтений на полях новозаветного текста, и особенное наречие. Историческая часть Ветхого Завета окончена книгами Товита, Юдифи и Маккавейскими, потом следуют Пророчества, и за ними Псалтирь, Притчи, Екклесиаст, Песни Песней, премудрость Соломона и книги Сираха и Иова. Далее непосредственно начинается Новый Завет без всякого предисловия. Сперва написаны Евангелия Матфея, Марка, Луки и Иоанна, потом послания апостола Павла к Римлянам, к Коринфянам, к Галатам, Ефесянам, Филиппийцам, Колоссянам, два к Фессалоникийцам и к Евреям, далее его же послание к Тимофею.

*Кроме книг, Товита, Юдифь и Маккавейских утрачены, все прочие исторические описания, и пророчества и пророчества Иеремии, Иезекииля, Даниила, Осии и Амоса.

**Смотри снимки между Син. видами

Russian Orthodox Bishop Porphiry Uspensky described the Sinaiticus manuscript in the 1856 book, Первое путешествие в Синайский Монастыŕ в 1845 году, detailing his 1845 visit to St. Catherine's Monastery at Mt. Sinai.

Following is the direct quote from the book, found on pages 225 - 226.

A professional English translation is given below the Slavonic. We are greatful to Baptist missionary to Ukraine, John Spillman for obtaining the initial translation with the help of an unnamed translator in Ukraine.

Further writings of Uspensky are currently being translated and prepared for addition to this page.

Following is the direct quote from the book, found on pages 225 - 226.

A professional English translation is given below the Slavonic. We are greatful to Baptist missionary to Ukraine, John Spillman for obtaining the initial translation with the help of an unnamed translator in Ukraine.

Further writings of Uspensky are currently being translated and prepared for addition to this page.

ENGLISH TRANSLATION

The best Greek manuscripts are stored in the priors' cells. There are only four of them and they are very precious for their antiquity, rarity and handwriting features, their content, the elegance of the beautiful faces of the saints and the entertaining drawings and paintings.

The first manuscript, containing the Old Testament which was incomplete* and the entire New Testament, with the epistle of St. Barnabas and the book of Hermas, was written on the finest white parchment in four columns of a long and wide sheet. Letters of the manuscript resemble the letters of the Church Slavonic very closely. Positioning of the letters was straight and solid (uninterrupted). There were no aspirates and accents above the words and no punctuation marks were inserted but for full points. The sacred text was written in four and two columns stichometrically with no space between the words so it seemed to be an indivisible utterance from full point to full point**. The way the sacred text was written, the positioning of columns and letters with the lack of grammatical prosody (versification), resembles the pattern invented by the Alexandrian deacon Euthalius about 446 AD. This was soon abandoned due to the many gaps between the columns on the expensive parchment. This means that the manuscript was published in the fifth century. The manuscript was notable in many ways, with a special order of the sacred books, intelligible exposition of the Psalms and the Song of Solomon, many interpretations on the margins of the New Testament pages and a peculiar dialect. The historical part of the Old Testament books finished with the books of Tobit, Judith and the Maccabees, which were followed by Prophets and then were placed the Psalms, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, the Song of Solomon, the Wisdom of Solomon, and the Book of Sirach, and Job. Further, the New Testament followed without any preamble. First came the Gospels; the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. Then the Epistles of the Apostle Paul; to the Romans, two Epistles to the Corinthians, to the Galatians, Ephesians, Philippians, Colossians, two to the Thessalonians, to the Hebrews, as well as the Epistle of Paul to Timothy, two Epistles to Titus and the Epistle to Philemon, then the Books of the Apostles followed, all the Canonical Epistles in our order and the Apocalypse and lastly the Epistle of Barnabas the Apostle and the Shepherd of Hermas were placed.

* All the historical annals and the prophetic books by Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Daniel, Hosea and Amos were lost, except for the books of Tobit, Judith and Maccabees.

**See images between Syn. types

The best Greek manuscripts are stored in the priors' cells. There are only four of them and they are very precious for their antiquity, rarity and handwriting features, their content, the elegance of the beautiful faces of the saints and the entertaining drawings and paintings.

The first manuscript, containing the Old Testament which was incomplete* and the entire New Testament, with the epistle of St. Barnabas and the book of Hermas, was written on the finest white parchment in four columns of a long and wide sheet. Letters of the manuscript resemble the letters of the Church Slavonic very closely. Positioning of the letters was straight and solid (uninterrupted). There were no aspirates and accents above the words and no punctuation marks were inserted but for full points. The sacred text was written in four and two columns stichometrically with no space between the words so it seemed to be an indivisible utterance from full point to full point**. The way the sacred text was written, the positioning of columns and letters with the lack of grammatical prosody (versification), resembles the pattern invented by the Alexandrian deacon Euthalius about 446 AD. This was soon abandoned due to the many gaps between the columns on the expensive parchment. This means that the manuscript was published in the fifth century. The manuscript was notable in many ways, with a special order of the sacred books, intelligible exposition of the Psalms and the Song of Solomon, many interpretations on the margins of the New Testament pages and a peculiar dialect. The historical part of the Old Testament books finished with the books of Tobit, Judith and the Maccabees, which were followed by Prophets and then were placed the Psalms, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, the Song of Solomon, the Wisdom of Solomon, and the Book of Sirach, and Job. Further, the New Testament followed without any preamble. First came the Gospels; the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. Then the Epistles of the Apostle Paul; to the Romans, two Epistles to the Corinthians, to the Galatians, Ephesians, Philippians, Colossians, two to the Thessalonians, to the Hebrews, as well as the Epistle of Paul to Timothy, two Epistles to Titus and the Epistle to Philemon, then the Books of the Apostles followed, all the Canonical Epistles in our order and the Apocalypse and lastly the Epistle of Barnabas the Apostle and the Shepherd of Hermas were placed.

* All the historical annals and the prophetic books by Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Daniel, Hosea and Amos were lost, except for the books of Tobit, Judith and Maccabees.

**See images between Syn. types

Some Thoughts on Information Gleaned From Uspensky

1) Uspensky is familiar with the Sinaiticus manuscript, including the New Testament and Barnabas and Hermas, as early as his 1845 visit. With this 1845 description, and the Russian communications and expeditions, and the books published by Uspensky in 1856 and 1857 (including the 1 Corinthians fragments), the communication with Avraam Norov, and other elements such as how Tischendorf wrote about the visit en route, the idea that Tischendorf did not know of the New Testament section when going to the monastery in 1859 should simply be discarded. And noted as part of the story "myths" (a nice word used by some, where fabrications would be more accurate.)

2) Uspensky describes a single manuscript (not loose leaves) contra the rescue report of Tischendorf re: his 1844 visit, in the accounts written 15+ years later. The manuscript, likely a codex, is in one piece, with:

"a special order of the sacred books"

Modern writers and textual theorists tend to a Tischendorf syncophant approach, or at the very least show a willingness to be duped. Even to the extent of affecting the manuscript science. Thus there is serious theorizing, without a shred of real evidence, that the ms. must have been feverishly found and rebound by monastery personnel in the 1844-1845 period. A far simpler explanation, fitting many evidences, is that Tischendorf had simply extracted the five quires and three leaves before it was seen by Uspenksy, and took them away as a heist. This was an accusation of the era (see Kallinikos in the Simonides correspondence, also notable is William Leonard Gage.) This is even a closer fit to his own 1844 private correspondence, where he simply talks about the leaves coming into his possession. 15 years later Tischendorf creatively made up a cover story, one that worked very well for his political advantage, and which is repeated even today by dozens of writers as if it were history.

3) There is no indication that Hermas was truncated. The book descriptions are quite well tuned. And an end-section of Hermas was found in the New Finds. Hermas was part of a major linguistic controversy in the 1850s involving Codex Athous (Lipsiensis), one of two editions published by Simonides in the 1850s. These controversies included an awkward linguistic retraction by Tischendorf of Latin linguistic elements, an accusation that could boomerang against Sinaiticus. We should consider the possibility that the manuscript was truncated in the years following 1845-1850. The New Finds locale, where many leaves appeared in 1975, being used as a discard dump.

4) The manuscript is fine white parchment. This is very different than the yellow and stained leaves taken to Russia in 1859. However, the description matches excellently the leaves that Tischendorf had taken out of Sinai in 1844, which was published as the Codex Friderico-Augustanus in 1846 and can be seen on the Codex Sinaiticus Project site today. Ernst von Dobschütz (1870-1934) similarly described these Leipzig leaves as "wonderfully fine snow-white parchment" in 1910. The description by Uspensky was a key element that led to examining the CSP images and noting that it supports strongly the accusation made c. 1860 that Tischendorf had darkened the leaves that were in Sinai (i.e. that had not gone to Germany in 1844.)

1) Uspensky is familiar with the Sinaiticus manuscript, including the New Testament and Barnabas and Hermas, as early as his 1845 visit. With this 1845 description, and the Russian communications and expeditions, and the books published by Uspensky in 1856 and 1857 (including the 1 Corinthians fragments), the communication with Avraam Norov, and other elements such as how Tischendorf wrote about the visit en route, the idea that Tischendorf did not know of the New Testament section when going to the monastery in 1859 should simply be discarded. And noted as part of the story "myths" (a nice word used by some, where fabrications would be more accurate.)

2) Uspensky describes a single manuscript (not loose leaves) contra the rescue report of Tischendorf re: his 1844 visit, in the accounts written 15+ years later. The manuscript, likely a codex, is in one piece, with:

"a special order of the sacred books"

Modern writers and textual theorists tend to a Tischendorf syncophant approach, or at the very least show a willingness to be duped. Even to the extent of affecting the manuscript science. Thus there is serious theorizing, without a shred of real evidence, that the ms. must have been feverishly found and rebound by monastery personnel in the 1844-1845 period. A far simpler explanation, fitting many evidences, is that Tischendorf had simply extracted the five quires and three leaves before it was seen by Uspenksy, and took them away as a heist. This was an accusation of the era (see Kallinikos in the Simonides correspondence, also notable is William Leonard Gage.) This is even a closer fit to his own 1844 private correspondence, where he simply talks about the leaves coming into his possession. 15 years later Tischendorf creatively made up a cover story, one that worked very well for his political advantage, and which is repeated even today by dozens of writers as if it were history.

3) There is no indication that Hermas was truncated. The book descriptions are quite well tuned. And an end-section of Hermas was found in the New Finds. Hermas was part of a major linguistic controversy in the 1850s involving Codex Athous (Lipsiensis), one of two editions published by Simonides in the 1850s. These controversies included an awkward linguistic retraction by Tischendorf of Latin linguistic elements, an accusation that could boomerang against Sinaiticus. We should consider the possibility that the manuscript was truncated in the years following 1845-1850. The New Finds locale, where many leaves appeared in 1975, being used as a discard dump.

4) The manuscript is fine white parchment. This is very different than the yellow and stained leaves taken to Russia in 1859. However, the description matches excellently the leaves that Tischendorf had taken out of Sinai in 1844, which was published as the Codex Friderico-Augustanus in 1846 and can be seen on the Codex Sinaiticus Project site today. Ernst von Dobschütz (1870-1934) similarly described these Leipzig leaves as "wonderfully fine snow-white parchment" in 1910. The description by Uspensky was a key element that led to examining the CSP images and noting that it supports strongly the accusation made c. 1860 that Tischendorf had darkened the leaves that were in Sinai (i.e. that had not gone to Germany in 1844.)